The Global Market Portfolio: The starting point for your asset allocation.

Many who aspire to be prudent investors have a portfolio they view as diversified, or passive, or both—when their portfolio is anything but.

It’s easy for the individual investor to allow hidden risk to sneak into his or her portfolio. Similarly, many investment products sold and promoted as being passive are, on closer inspection, making active bets on the market. There’s nothing wrong with making an active bet if you’re aware of your choice, conduct your due diligence, and know what you’re doing. But thinking you have a passive and diversified portfolio when you do not can lead to a false sense of complacency.

The Global Market Portfolio is a great way to rectify the situation and reduce the hidden risks and active bets, that may be lurking in your portfolio.

If you’re not global, you’re not truly diversified (or for that matter, passive).

There is an argument to be made for active investing. Although he preaches a different tune now, Warren Buffett made his fortune, in part, through smart, concentrated bets. For those who are good at it and do their homework, value investing works by identifying undervalued assets and then sticking with them, often against the tide of popular opinion. However, there are millions of investors, with billions of dollars, all over the world competing with one another in attempt to find these value investments. In this zero-sum game, only the most skillful survive.

Active investing requires a lot of work, insight, and monitoring. It is definitely a full-time job. Even those who are paid to do it for a living often fail at it. By now, most investors are familiar with the many studies showing that the vast majority of active fund managers (even though they may have a hot year or two) underperform the market and relevant benchmarks over the long run (see here for more).

Amidst growing skepticism about active investing, the late Vanguard founder, John Bogle, carved a niche as perhaps the foremost proponent of passive investing. The most diversified portfolio, he correctly asserted, is a passive one. “Don't look for the needle in the haystack,” Bogle famously said. “Just buy the haystack!”

What does it mean to just “buy the market (or the haystack)”? It essentially means to invest in assets in direct proportion to how the market currently values them—in other words, in a portfolio weighted by total market value. Doing so allows you to own your own tiny slice of the total market pie. There may be years when active investors outperform a passive portfolio. But over the long haul (and passive investing is very much a long play), you will come out ahead.

So how does one go about “buying the market”? Bogle revolutionized investing by introducing the index fund—a mutual fund designed, not to beat the market, but to mirror or replicate it. An index fund tracks a large cross-section (or index) of the market by owning all of the assets listed therein, in amounts weighted by total market value. For example, if Apple’s market capitalization is 2% of the total market of the top 500 U.S. companies, the S&P 500 index fund would own 2% of Apple stock. As that capitalization shifts (when some assets outperform others), the index fund shifts with it. It is married to the market.

Index funds are a low-cost and efficient way of owning a substantial chunk of the market. An S&P 500 index fund, for example, is a pretty good proxy for the U.S. stock market as a whole. The problem is that investors have been led to believe that owning an S&P 500 index fund, along with a U.S. bond fund, brings them reasonably close to a diversified, passive portfolio—when, in reality, they are falling far short of that goal.

The U.S. market does not exist in isolation, but as part of a larger global market. For example, U.S. stocks account for only 44% of total world equities. If U.S. stocks are the only equities in your portfolio, you are in essence betting on the U.S. stock market and against the rest of the world. In a global portfolio, your risks would be spread across all markets. If the U.S. market slumps, those losses might be offset by gains in emerging markets. Your equity eggs would not all be in one national basket. But if your sole equity investments are domestic funds, you will be disproportionately exposed to the risk of the U.S. stock market as a whole.

The U.S. bond market accounts for even less of the global market, only 36%. You get the point: A portfolio of domestic stock and bond index funds is anything but diverse, anything but passive. You may assume you are playing it safe by sticking with a domestic portfolio. But instead, you are inviting greater risk. Some might argue that, in hindsight, the US has had a better risk/reward than a global portfolio, but that does not mean this will persist going forward.

How can you buy a Global Market Portfolio?

At first, this portfolio was just an idea, a theoretical construct. In 1958, Nobel prize-winning economist James Tobin posited that there exists what he called a single “super-efficient portfolio” that was the perfect balance between risk and reward. You could alter the portfolio to go after higher returns, but the greatly increased risk would not be worth it. Or you could lower risk somewhat, but at such a sacrifice to returns that you might as well go with a risk-free asset (e.g., T-Bills).

In 1964, economist William Sharpe argued that Tobin’s super-efficient portfolio was the Global Market Portfolio, which would be composed of all risky assets proportionally weighted by their total market value. Tobin and Sharpe created the intellectual foundation for the index fund movement, which began in the mid-70’s with the launch of the Vanguard Fund.

But as we have seen, individual index funds don’t come close to even approximating a Global Market Portfolio, and there are some who contend that such a portfolio still exists in theory only. In 1977, economist Richard Roll wrote a critique arguing that a true market portfolio would include every risky asset: not only stocks and bonds, but also real estate, commodities, collectibles, and anything else of value that could be traded. In short, he argued that a Global Market Portfolio is an interesting but unachievable ideal.

Since then, numerous economists have tried to pin down the Global Market Portfolio. Sharpe himself proposed what he calls a World Bond/Stock Portfolio (composed of four Vanguard index funds) that he says comes reasonably close to the real thing, and is the most realistic option for the average individual investor. Sharpe called on Vanguard to create a single consolidated index fund that would address the same goal, but that hasn’t happened yet. A number of wealth management companies have stepped up with their own products that approximate a Global Market Portfolio.

Challenges (and advantages) of global investing for the individual investor.

Putting together a Global Market Portfolio, or something that comes reasonably close to it, can be a daunting task for the individual investor. Moreover, although such a portfolio would, in its purest form, be one that re-balances on its own, real-world approximations require careful monitoring and adjustment. So, if you’re going to go this route, rely on an advisor or a wealth management company that specializes in this kind of portfolio. Our firm is certainly an option to consider as this investment approach lies at the core of our investment philosophy.

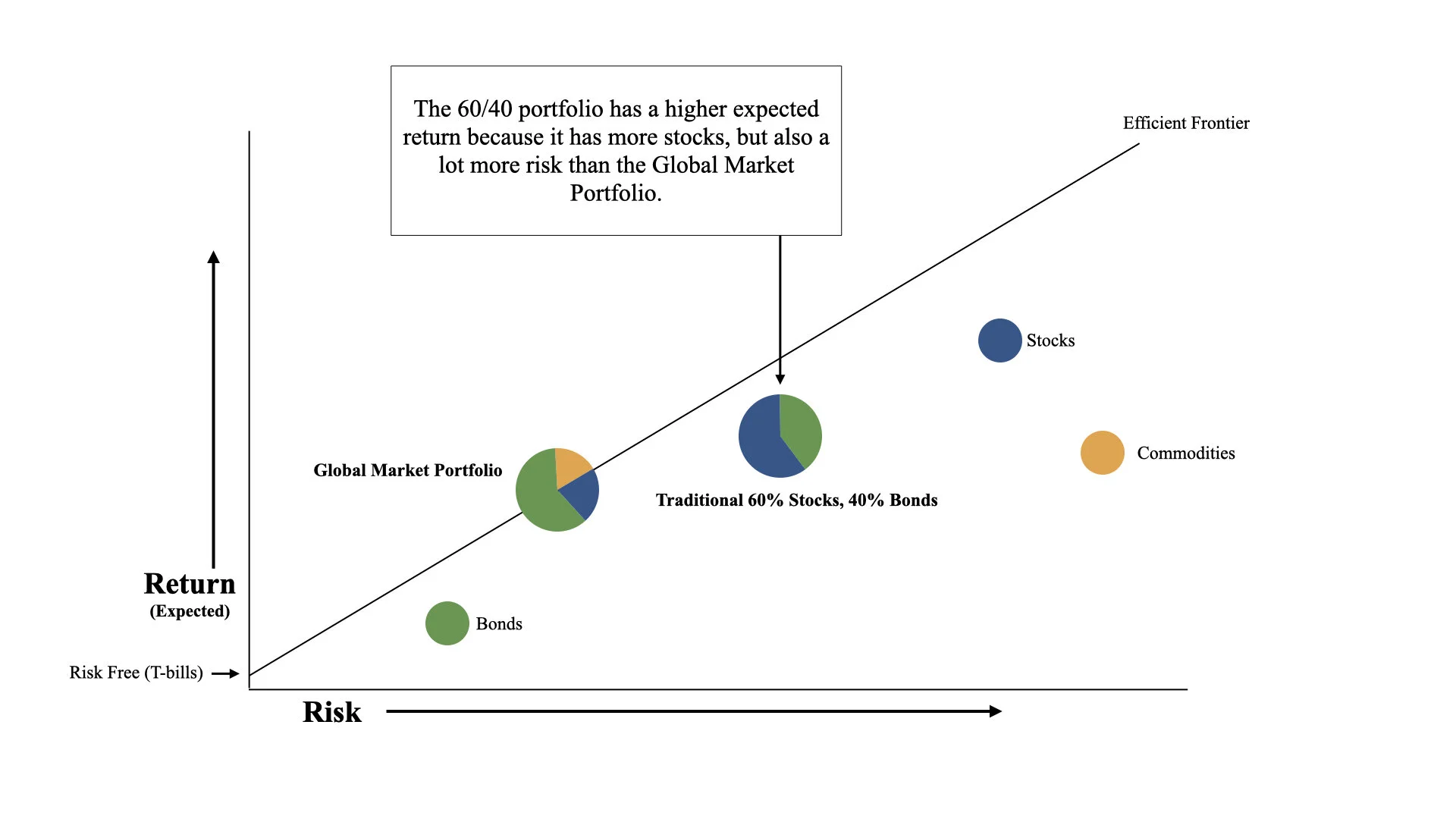

The other big challenge is modest returns. While a Global Market Portfolio gives you maximum diversification and will reward patient investors in the long run, it will underperform more active, targeted strategies in the short term. And its long-term returns are not overwhelming. According to one study, in the years 1960 to 2017, a market portfolio realized a compounded real return of 4.45%, or 3.39% above the riskless rate. To illustrate how this risk return is compared to other more classical portfolios take a look at the below chart.

Notice how the Global Market Portfolio has a lower overall risk return compared to a 60/40 (60% Equities, 40% fixed income). However, also notice how the 60/40 portfolio has a higher expected return. This is explained by the higher risk and is the main reason investors prefer a 60/40 over a more diversified Global Market Portfolio.

One way to compensate for those modest returns is to “tilt” the portfolio toward factors, such as value, momentum, small caps, etc. that would give a higher expected return (and of course higher risk). But that would involve essentially abandoning the idea of passive investing.

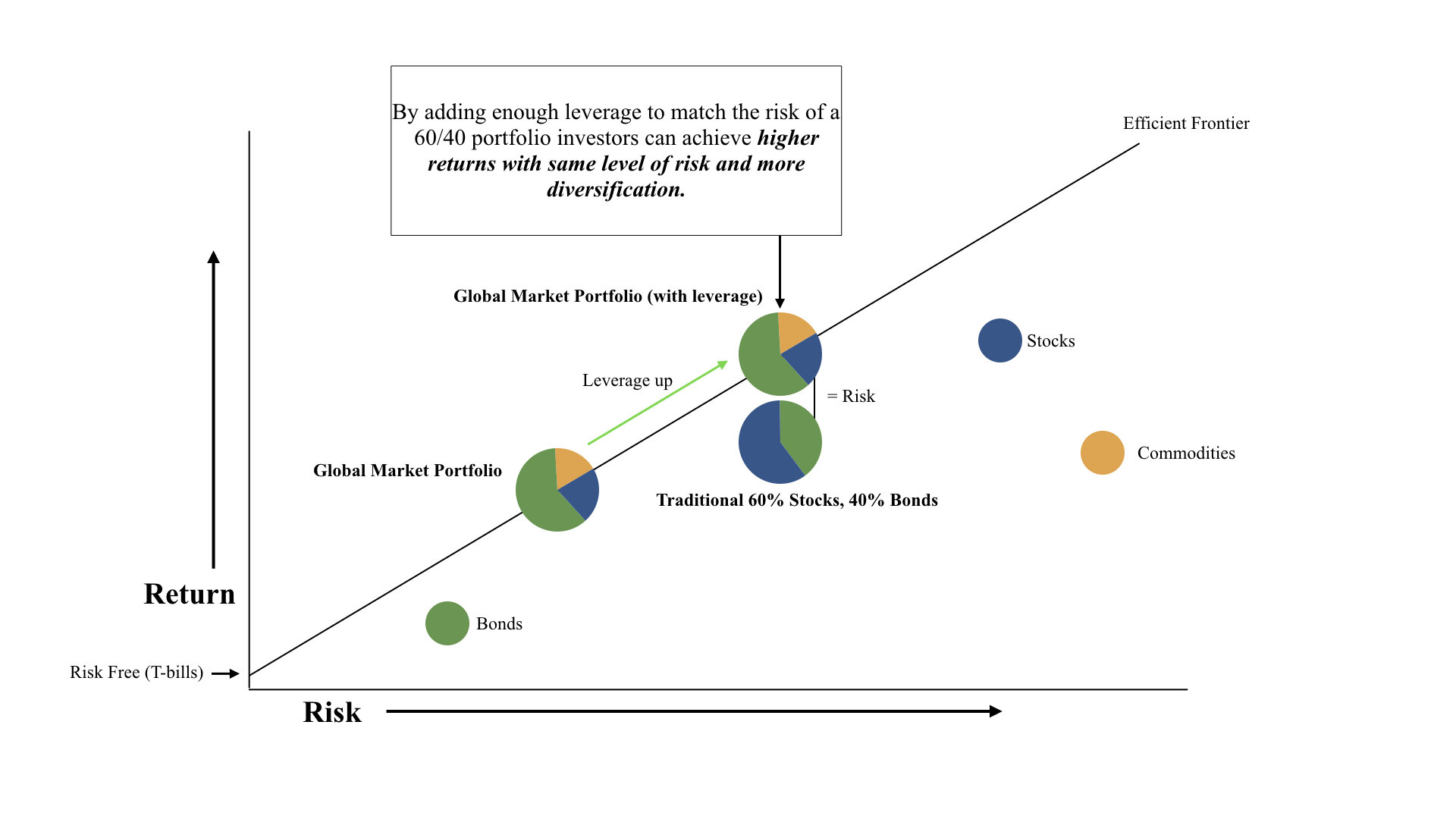

A better option is to use leverage to increase returns. As discussed in our previous post, using leverage (especially with low-risk assets like bonds) can significantly improve returns with minimal increase in risk. Using leverage on a Global Market Portfolio also avoids having to make a bet that one asset class, country, or region will outperform another. In other words, you are taking on more risk (through leverage) and thereby increasing your expected returns, without having to make a bet.

There are many advantages to owning a Global Market Portfolio. You essentially avoid all of the dynamics that behavioral economics tells us lead to the biggest investing mistakes:

· You are not trying to predict or time the market.

· You are not trying to pick winning stocks or decide which assets are undervalued or overvalued.

· By keeping trading to a minimum, you avoid excessive trading costs and active management fees.

· Last but not least, such a passive strategy leaves you far less vulnerable to making the kind of emotional, impulsive decisions that doom so many investors trying to outsmart the market.

If you’re in it for the long haul, marrying the market (as opposed to trying to beat it) is a more dependable strategy, and one which will help you sleep better at night.