YEAR-END REVIEW & THE ROAD AHEAD

By: Julio Cacho, Ph.D.; Cole Conkling, J.D.; and Juan Carlos Herrera (This post contains opinions of its authors)

With 2020 just behind us, it’s time to reflect on what the markets did last year, the risks ahead, and how you should think about positioning your portfolio for the years to come. 2020 was obviously a year that will never be forgotten in the markets for myriad reasons—huge drawdowns; lots of uncertainty, which caused gut-wrenching volatility; and unprecedented socio-political upheaval. Nevertheless, if you had the fortitude to withstand the volatility and were adequately diversified, your portfolio should have grown at a respectable clip.

Unfortunately, a simple change in the calendar did not alter our current struggle with COVID-19, even though a large-scale vaccine rollout is on the horizon. Add to that a new President and Congress, and there’s certainly enough uncertainty to affect markets in 2021. But here’s the thing: The future (and, likewise, any “market”) is always uncertain. That’s the name of the game, so get used to it. Not a single prognosticator at the end of 2019 predicted a global pandemic that would rock markets in 2020. Many now claim that their forecasts were terribly wrong, not because of any fault of their own, but because of COVID-19, which is something that they “never could have predicted.” Very true indeed, but that’s exactly the point: Unpredictable things, like COVID-19, happen with regularity and will no-doubt happen again and again during our investment lifetimes. So, if we know that large-scale, unpredictable events will happen again, but have no idea what those unpredictable events will be or when they’ll occur, what should we do? We’ll get to that later, but first let’s dive into what the markets actually did do in 2020.

2020 Public Markets’ Performance

Figure 1 below nicely shows what many asset classes did in 2020, with the added benefit of depicting each asset’s maximum drawdown (light green) and overall gain or loss (dark green):

Figure 1: Source: Visual Capitalist https://www.visualcapitalist.com/how-every-asset-class-currency-and-sp-500-sector-performed-in-2020/

Past Performance is not necessarily indicative of future results.

As you can see, U.S. large cap. stocks did good, returning over 15%, well above their historical yearly average of around 8%. Small caps and emerging markets also did nicely (18.5% and 14.6%, respectively), while developed markets (e.g., Int. Developed Stocks) comparatively struggled at 5.3%. And you might be surprised that corporate bonds and U.S Treasuries both turned in positive returns (9.7% and 3.6%, respectively). U.S real estate struggled for the year, down 8.4%. Commodities overall also dipped, losing 6.6% on the year.

But what’s most interesting about this year’s returns are the maximum drawdown percentages for each asset class. For example, for you to have received a 15.5% return on U.S. Stocks for the year, you’d have to have withstood a 32.5% drawdown! Not an easy task in real time. Volatility and drawdowns are a fact of life in any market, and booking high returns usually means you’ll have to withstand some serious pain. That’s the “fee” for getting high returns from risky assets like stocks.

THE RISKS AHEAD

As we enter 2021 investors should be short-term pessimists, but long-term optimists. Our world is uncertain, and we are no doubt entering uncharted waters, especially in the short-term. Predicting where the markets will go next month, this year, or even next year is a fool’s errand. Countless academic researchers have empirically proven this, and our own experiences confirm it.

For example, say that at the end of 2019 you knew with 100% certainty that a pandemic was coming in 2020, what would you have done? You might have reasonably thought that shorting the S&P 500 would make you a lot of money. However, as we now know, the S&P recovered and turned in a 16% return for the year! So, even knowing that major events will occur doesn’t tell you how markets will react to them. Human beings—and by extension economies and markets—are resilient and adaptable. The unthinkable (i.e., wearing masks, quarantining for months on end) quickly becomes normal. Some un-sinkable companies go under, while newcomers explode onto the scene. The story of human progress and economic advancement marches forward. Great investors must be long-term optimists, believing in the productive capacity of the human species to continually advance, while knowing the road to that advancement is anything but straight and narrow. One key to reaching the mountaintop is knowing the risks along the way that might make us fall, lengthen our climb, or cause us to tap out—exhausted, broken, and without the resources to continue to the peak. In investing, there are two main risks to understand and prepare for: Idiosyncratic risk and systematic risk.

Idiosyncratic Risk vs. Systematic Risk

Idiosyncratic risks are those that are specific to individual assets, regions, and companies. For example, the risk of a CEO making a bad decision that imperils the company. The accountant that “cooks the books.” The insurance policy that didn’t cover the damage. These risks are real and never-ending, so you might think you’ll get compensated because “risk and return are inextricably linked.” But sadly, you are not. Why not? Because these risks can be diversified away and eliminated. And if you can eliminate a risk, you will not be compensated for taking that risk.

You can eliminate the risk of ABC Co. having a bad CEO by investing in other companies within ABC Co.’s sector. So, if ABC Co. shutters, other companies in its industry will absorb its market share. And if the market cap. of the sector as a whole goes up, your investment in the sector will too. You didn’t need to concentrate all your money in ABC Co. to obtain the sector’s return. You took on risk that you could’ve diversified; therefore, that risk will not be rewarded. Now, ABC Co. could have instead had a great CEO, and outperformed its competitors in the sector and made you a great return. However, this excess return was due to luck and not for a risk that was being compensated for pre-investment. The risk that the CEO would be bad always existed, it just never materialized.

Systematic risks are ones that affect the entire market and that cannot be eliminated through diversification. Examples include recessions, pandemics, and war. These are risks you should expect to be compensated for because you can’t diversify away the risks.

Take on the Right Risks (Ones you expect to be compensated for)

Our mission is to give you the highest probability of achieving a given expected return based on your risk tolerance and financial goals. Because most of you have too much idiosyncratic risks in your businesses, private investments, and day to day lives, and since you are not compensated for taking more idiosyncratic risk, we should only focus on how much systematic risk you are willing to take (https://www.capitalsurge.com/2017/08/22/why-do-investors-not-get-compensated-for-diversifiable-risk/). Idiosyncratic risk goes down as diversification goes up; therefore, a maximally diversified portfolio of all publicly available asset classes, from all regions, countries, sectors, and industries will virtually eliminate idiosyncratic risk. This can all be accomplished by owning a market portfolio of all asset classes. We will call this market portfolio going forward a “Global Market Portfolio.”

If you would like to take a deeper dive into understanding these types of risk, we highly encourage you to listen to the following podcast:

GLOBAL MARKET PORTFOLIO

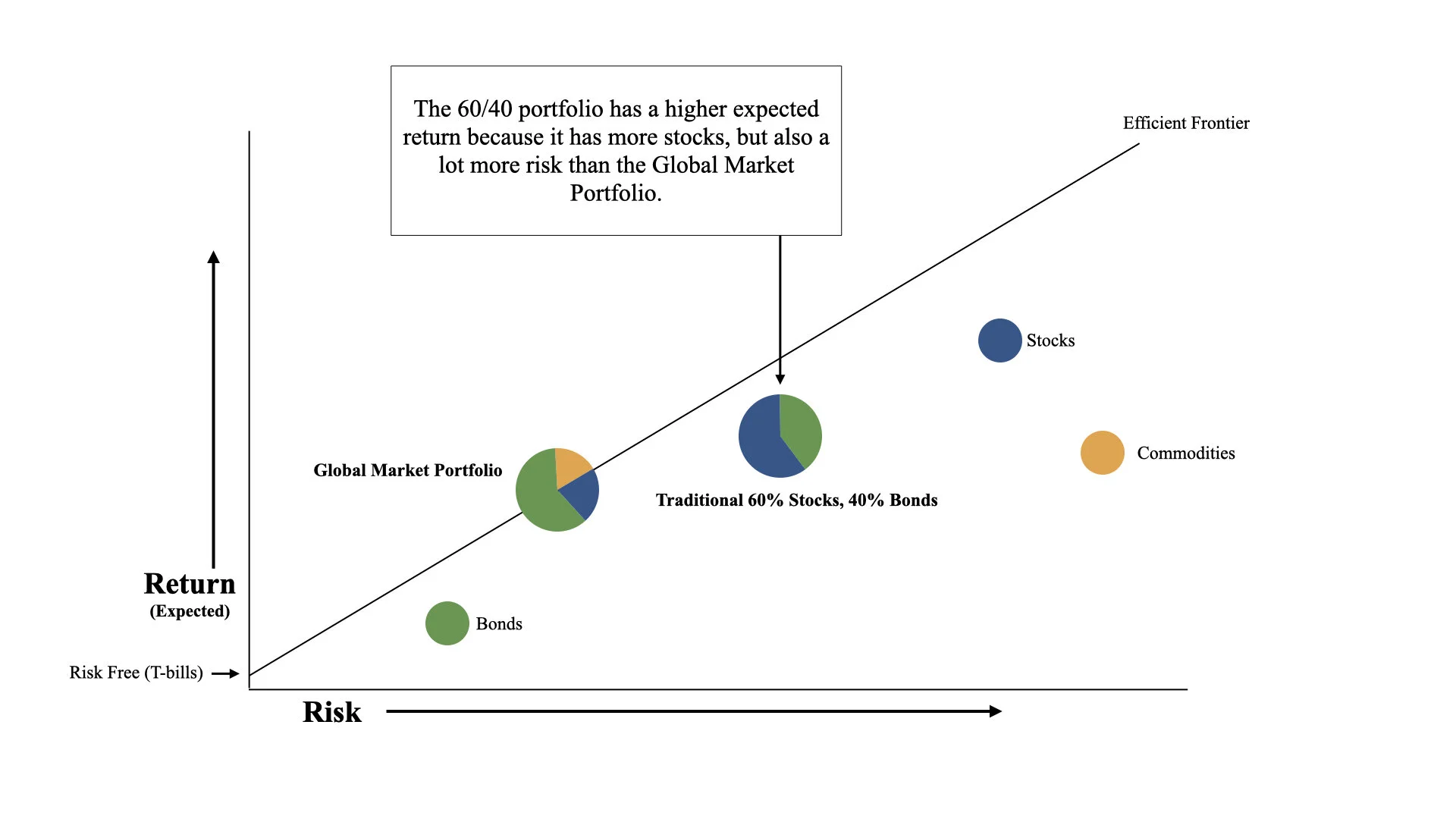

A Global Market Portfolio (“GMP”) is a bundle of investments that includes every investable asset available in the world (e.g., stocks, bonds, commodities, and real estate), with each asset weighted in proportion to that asset’s presence in the overall global market. A GMP is thus “market-cap. weighted.” For example, if bonds make up 50% of the investable assets available in the world, a properly weighted GMP would hold 50% bonds. A touchstone of the GMP is that it defers to all the world’s investors to determine the percentage of each asset in the portfolio—it does not bet on (or “tilt”) to one asset class over another based on anyone’s prediction of what might occur in the future. Compare that to, for example, a typical 60/40 stock/bond portfolio, which over-weights stocks, under-weights bonds, and excludes commodities altogether. If bonds outperform stocks, or commodities outperform both stocks and bonds, a 60/40 portfolio could materially underperform.

The GMP only has systematic risk in it and is the ultimate passive portfolio because it simply tracks the overall performance of the global market of investable assets without trying to bet which asset class, sector, region, or country will do best. Theoretically, it’s one of the safest portfolios you can own because of the amount of diversification. And since you own all of the assets in the world, you don’t care about which asset classes, regions, countries, or sectors do best. For example, if capital flows from the U.S. to China, your U.S. holdings will decline, but your China holdings will increase without you doing anything. There will, therefore, be no unnecessary buying and selling based on where you (or the “experts”) think the markets are going. As the late Jack Bogle (founder of Vanguard) famously quipped: “Don’t look for the needle in the haystack, just buy the haystack.” The GMP is the “haystack.” It should be the centerpiece of every investor’s long-term portfolio.

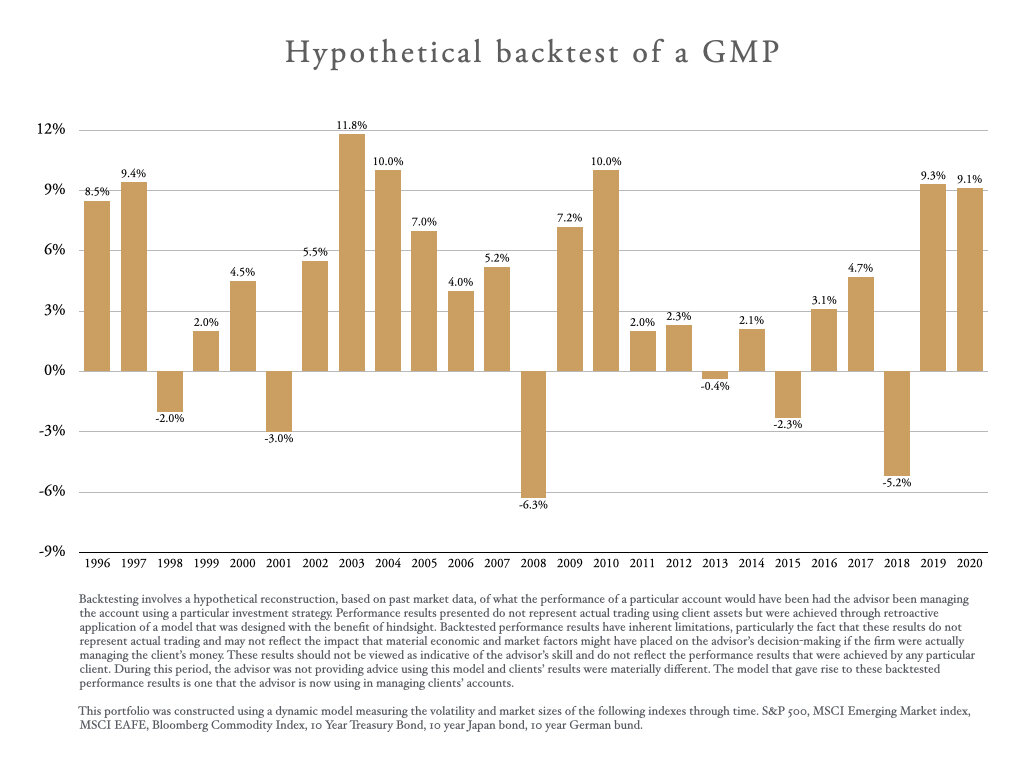

Nevertheless, because the GMP is so diversified (and thus should have low volatility), the returns might not be enough to accomplish many investors’ goals. A close proxy for a GMP can be constructed using publicly-traded index funds or exchange traded funds (ETFs). Historically, the average annual return of this GMP investable portfolio has been 3-6%. This is good for investors trying to protect wealth, while maintaining real purchasing power, but not ideal for investors looking for long-term growth. Keep in mind that 3-6% has been the average annual expected return going back more than 20 years; for the year 2020, the GMP returned just above 9%. Please see below for year-by-year performance since 1996.

Figure 2: Past performance is not necessarily indicative of future results. The risks of trading in futures and options products can be substantial.

Increasing Risk & Return Above the Global Market Portfolio

Investors seeking returns greater than the GMP’s have essentially three options: (1) change the GMP’s asset allocation to riskier assets (e.g., less bonds, more stocks); (2) keep the asset allocation the same as the GMP’s, but substitute riskier assets within each asset class (e.g., instead of lots of government bonds, substitute high yield/junk bonds, but still own the same percentage of bonds the GMP owns); or (3) keep the GMP’s asset allocation the same, but apply leverage to achieve higher risk and expected return. Of the three, Option 3 is the most optimal because it has the highest probability of achieving its expected returns over the long term. This is where our flagship fund, The Quantor Core Fund, LP, comes into focus.

Figure 3: (Option 1) Changing the GMP’s asset allocation to riskier assets. Past performance is not necessarily indicative of future results. The risks of trading in futures and options products can be substantial.

Figure 4: (Option 3) Keep GMP asset allocation the same, but apply leverage to achieve higher risk and expected return. Past performance is not necessarily indicative of future results. The risks of trading in futures and options products can be substantial.

The Quantor Core Fund, LP

The first two options are not ideal because they introduce idiosyncratic risks to the portfolio, which will not be compensated. Option 3, leverage, is the only option to keep the portfolio free of idiosyncratic risk. Moreover, leverage acts like a dial that you can turn up or down to match your risk tolerance, while keeping your underlying portfolio maximally diversified and free of idiosyncratic risk. Our flagship fund, The Quantor Core Fund, leverages the GMP to match the risk of a 100% stock portfolio, but with higher expected returns. Those higher expected returns, however, come with higher volatility (risk) that must be stomached. Below is an illustration.

Figure 5: The Quantor Core Fund, LP matching the risk of public equities. Past performance is not indicative of future results.

For more information on the Quantor Core Fund, LP please see our fund fact sheet and investor deck by clicking one of the links below. If you don’t have the password you may request one by filling out the form below and our team will be in touch.

CLOSING THOUGHTS

Figure 6:

Returns are based on price index only and do not include dividends. Intra-year drops refers to the largest market drops from a peak to a trough during the year. For illustrative purposes only. Returns shown are calendar year returns from 1980 to 2020, over which time period the average annual return was 9.0%.

Guide to the Markets – U.S. Data are as of December 31, 2020.

There’s unfortunately no “free lunch” when investing: Risk and return are inextricably linked. If you want high returns, you’re going to have incur high risk, whether you know it or not. And if you want low risk, you’re going to probably get low returns. In 2020, if you invested in stocks and stuck with it, you saw good returns, but had to deal with extreme volatility (a form of risk) along the way. Indeed, if you invested in practically any asset (private or public), you probably had moments of sheer terror wondering whether that asset’s future return would still be what you expected in a pandemic and post-pandemic world.

Risk (specifically, idiosyncratic risk), however, can be reduced—and a sort of “free lunch” can actually be had—by the simple act of diversification. This has been proven time and time again by robust academic research and is the cardinal tenant of long-term investing. The GMP is a very well diversified portfolio and a great way to easily achieve diversification with low risk. The Quantor Core Fund is similarly well diversified, but has higher risk due to the leverage and, with that, higher expected returns. If you can withstand the volatility, it’s a great long-term option to consider.

In closing, it’s important to remember that although 2020 was filled with uncertainty and volatility, this was not unusual. Every year is filled with uncertainty— 2021 will be too. For example take a look at the S&P 500 intra-year declines vs. calendar year in figure 5.

The key to being a successful investor is preparing for that uncertainty through realistic and robust planning, followed by the creation and maintenance of a portfolio this is as maximally diversified as possible. “As possible” is the key phrase here. Nobody is perfect, and a perfect portfolio probably only exists on a spreadsheet. The most important thing, therefore, is to have a financial plan and portfolio that you believe in and can stick with through thick and thin. This is a long game and the longer you’re in it the better you’ll likely do.